Book Review - Understanding Michael Porter by Joan Magretta

The connection between psychological growth and strategic thinking

Michael Porter is famous for making lots of extremely influential contributions to how we think about strategy. From what I gather, his work is considered mandatory reading in most MBA programs. You know a scientist has become famous and influential when their surname becomes a unit of measurement (e.g. Kelvin, Fahrenheit, Watt, etc). But you know a business think has become famous and influential when their ideas are regularly misquoted or misunderstood on Twitter.

Understanding Michael Porter by Joan Magretta is an overview of Michael Porter's broader academic work. If you don't have an MBA background or are just otherwise interested in strategy, I'd highly recommend reading it. I was inspired to read this book after attending Shreyas Doshi's Product Sense course. If you haven't done that, I'd highly recommend that you do it too.

It's particularly relevant to the overall research project I've been circumambulating - What would it take to build an AI system that can autonomously imagine, brainstorm, build and run an entire software company. Specifically, for it to do all this while maintaining a competitive advantage and having its actions be considered legible and reasonable to the humans that own it.

This project is my attempt at integrating my interest in AI, "capitalism", psychology, philosophy and personal transformation via spiritual practices. At least to me, it seems impossible to safely and effectively make progress on such a project without a skillful integration of all of these disciplines.

My preferred doorway into this project has been the thought-experiment of a single-person company. I briefly introduced this thought experiment in this previous post on the hero's journey of a founder CEO. Rigorously mapping out the cognitive machinery necessary for a human to instantiate and participate in such a company seems like a good "baseline". Once we have such a description, it'll be a lot easier to compare and contrast this description against existing AI systems. Such an analysis would motivate targeted evaluations for existing systems, and better inform wiser human-AI interaction.

I've also noticed that a lot of business books explain how managers can improve the overall strategy and operations of their firms. There's also a lot of self-help books which provide guidance on how one can grow in their career, either as a manager or an IC. However, I've seen very few books that provide a synoptic integration of both of these concerns to a level of detail that I find satisfying. The thought experiment of a single-person company could be the doorway for such an integration. That is, perhaps it could shine a light on the causal connection between the firm's commercial outcomes and the internal psychological dynamics of its employees.

There's quite a lot that can be said about all of these topics. This specific post connects strategic thinking at the level of the entire firm, with each individual employee's ability to think strategically. The minimal example for exploring such a connection is a single-person company. Future posts will expand this connection to firms with multiple employees. Ditto for the implications of all of this on the development of my hypothetical AI.

What is a "strategy" and what is its purpose?

I've seen the word "strategy" thrown around a lot. I've seen it encompass everything from low-level task lists, to quarterly plans to extremely high-level and vague vision docs designed to make some VP look good. I like that Porter provides an extremely concrete definition of what he means by strategy. I especially love that he seems to do so with a very "first principles" approach.

To Porter, a firm is a social organism that should be oriented towards a crisp quantitative definition of value. More specifically, he assumes that that a firm is engaged in a series of activities (i.e. its value chain) that eventually generates value for some sets of buyers. The firm then captures some fraction of this value to keep itself alive. He wrote this as a professor of business. So it seems reasonable that he chooses to articulate the value that firms capture as profit (i.e. Profit = Price - Cost). It's worth pointing out that his framework can be readily applied to non-profits, if it's possible to quantify their value-add in some other way.

There's a Q&A at the end of Understanding Michael Porter which I found extremely insightful. In it, I got the sense that he that he has a strong preference for profitability since it's the most "real" metric that one can optimize for. Having said that, his overall framework seems quite agnostic to what "value" means for you. That is, so long as you can unambiguously quantify it. In this post I'll assume that our theoretical single-person company is trying to optimize its profits over time.

A firm is said to have achieved competitive advantage if it is able to sustainably generate profits that exceed whatever the industry average is. A firm can attempt to either engage in differentiated activities or improve its operational effectiveness to generate returns greater than the industry average. When a firm engages in differentiated activities, it seeks to achieve atypical returns by engaging in fundamentally different activities (i.e. value chains) from its competitors. Operational effectiveness involves a firm keeping its overall set of activities stable, but just performing them far more effectively and efficiently.

Let's explore a concrete example around the manufacture of chairs. Suppose that the market contains an incumbent company that buys its lumber from some wholesaler, works on it in their warehouse and then sells the chairs via Etsy. For whatever reason, we'd like to get into the chair business. Broadly speaking, we have two options. We can either "compete to be different" or we can "compete to be the best".

The naive option would be for us to "compete to be the best". That is, to simply copy the existing set of activities that the incumbent is doing by trying to do them more effectively to squeeze out profits. For example, we could assemble our chairs essentially the same way but use some new method of sawing that cuts the wood ~3% faster. Or we could use essentially the same marketing channels segmenting the same customers, but design a better advertisement that lets us sell each chair for ~5% more. These overall efficiencies would allow us to charge lower prices or sell something slightly better than the incumbent to keep our company alive. This naive option is extremely reliant on retaining institutional knowledge, protecting trade secrets, public IP protection, etc to help protect this fragile profitability. For specific industries this profitability could be fragile indeed! If some key employees leave for the incumbent and take our secrets with them, or if the incumbent innovates their way to an equivalent set of secrets we'd lose our margins. Assuming that we continue to compete to be "the best", we'd end up in an equilibrium where our margins have been steadily competed away. Where our profits have regressed to some mean characterizing that overall market.

Porter instead recommends that firms should "compete to be different". That we should engage in a fundamentally different set of activities from any of our competitors while nevertheless achieving profit. In an ideal world these activities would be so different that the incumbent simply couldn't engage in them even if they wanted to. Or wouldn't engage in them without substantially compromising their existing value chains making imitation pointless from their perspective. These natural trade-offs provide barriers against imitation that are more effective at protecting competitive advantage than mere operational effectiveness. To be clear, Porter doesn't dismiss the importance of operational effectiveness. But the primary aim of each firm should be to establish some differentiated activities as soon as possible. And then increase efficiencies within that position to squeeze as much profit as possible. This affords the creation of a far more stable feedback cycle which allows the firm to expand its position and power.

To Porter, a strategy is an overall policy that offers normative guidance on the set of trade-offs that a firm should make when constructing its value chain. That is, a good strategy expresses a clear opinion on what the firm should do as well as what the firm shouldn't do when constructing its value chain. By implication, a good strategy offers insight on the sorts of customers that a firm should seek to satisfy. As well as the sorts of customers that are explicitly a non-goal for the firm to satisfy. And perhaps the sort of customers that should be explicitly repelled. That is, the heart of a good strategy is the extent to which it clarifies and justifies crisp trade-offs and constraints.

A common and damaging anti-pattern that strategists can fall into is straddling multiple positions in the marketplace. That is, attempting to defer or avoid clear trade-offs that undermine the firm's ability to build power in either position. It's the corporate version of a firm attempting to please everyone causing it to please no one. Like any individual, the firm is limited in space and time. It has a finite set of resources. Absence of clarity around trade-offs and constraints wastes these resources. It negatively impacts the extent to which the firm can experiment engaging in differentiated activities, ultimately undermining its competitive advantage. I've been grateful to work in many organizations with extremely brilliant and competent ICs and managers. A number of these organizations went sideways because their leaders couldn't agree on a clear strategy for that organization. Almost always, these organizations fumbled because its managers couldn't resolve their differences or otherwise attempted to straddle multiple strategic positions.

Once a firm has a coherent strategy, it's imperative that this strategy is relentlessly communicated both inside and outside the company. There's an innumerable number of decisions that the firm's employees need to make everyday. Habituating the strategy within their psyche makes it easier for them to realize actions that are more relevant within the overall spirit of the strategy. Clearly communicating the strategy externally allows analysts, etc. to appropriately benchmark the business. It allows rational competitors to understand what they should avoid doing to destroy each other's respective margins in a corporate version of mutually assured destruction. Of course in practice, there's some nuance to all of this. However, I've found that many companies, organizations and teams that I'm aware of in tech fail due to under-communicating their strategy rather than over-communicating it. The dirty laundry in many organizations is that they simply don't have a strategy in the form that we've described it here.

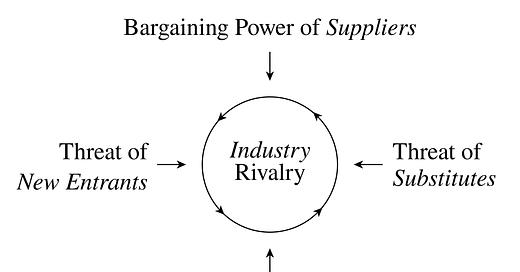

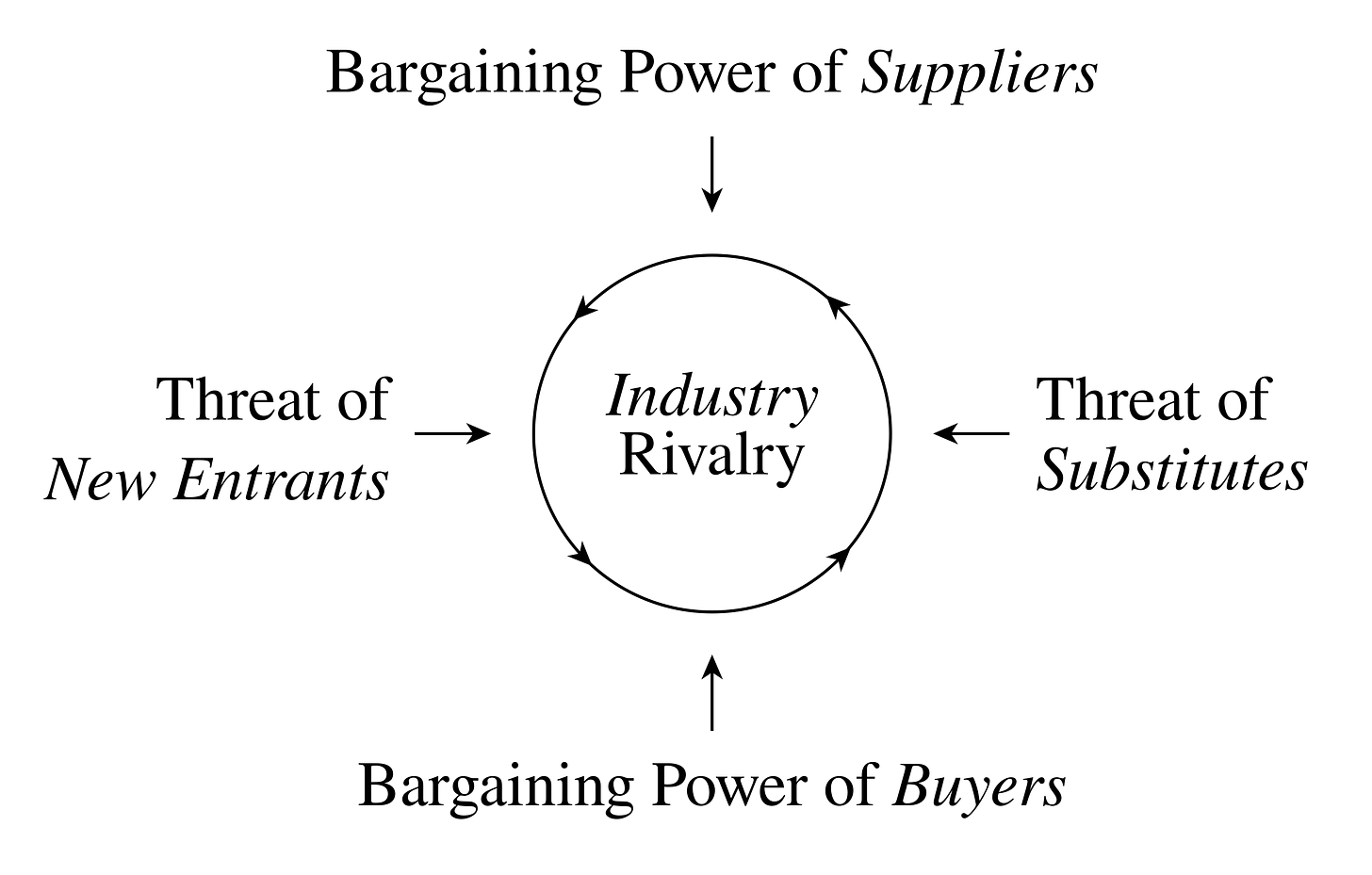

Porter’s Five Forces

Porter's Five Forces analysis is a framework to drill down into the dynamics of the business, its environment and the relationship between the two.

Conceptually, it's quite simple. It starts with the equation: Profit = Price - Cost. And then attempts to deconstruct the overall dynamics of the business, its market environment and the relationship between the business and its environment to consider what might influence an overall business's profitability. For example, this analysis can help create clarity around whether a business is in a market that fundamentally engenders perfect competition. Or whether it's in a market whose natural structure affords substantial differentiation.

As the diagram above shows, the five forces can be articulated in five fairly general questions:

To what extent can our buyer's willingness to pay be affected by cheaper substitutes? Note that these cheaper substitutes are considered fairly broadly. We don't stop at "direct" substitutes. But rather, we also the myriad other ways that the buyer might perform the same "job to be done" in cheaper ways.

What is the activation energy necessary for new entrants to spring up? Our margins are everyone else's opportunity. To what extent do we have natural defense mechanisms against competition via regulatory barriers, high switching costs, etc?

How much influence can our buyers exert on our ability to increase our prices? For example, in an extreme case, is the overall market a monopsony where there's only one buyer and multiple sellers?

To what extent can we exert influence on the suppliers of our raw inputs to lower our costs?

How much competition is there between existing firms in this overall market? For example, is it an extremely competitive space characterized by continuous price cuts and increases in customer acquisition? How concentrated is the market and is it fairly dynamic or fairly stable?

Some thoughts on "entrepreneurship"

I really like Porter's "first principles" attitude of coming up with a clear objective function (i.e. profitability). And then subsequently working through the internal and external factors that might influence our ability to maximize this objective function. If what you care about is profitability, then just because a market is growing quickly doesn't mean that it's a good market. On the flip side, just because a market is fairly static doesn't immediately mean that it's a bad market. In a Q&A at the end of the book, Porter explicitly calls out that there are natural limits to growth from a given position within a marketplace. In fact, unnaturally over-extending from this position can be delusional, often leads to straddling, and can end up destroying value.

Of course, in actuality, the world is fairly nuanced. But I've found myself increasingly resonating with this overall attitude. During my formative years, "entrepreneurship" has often been associated with high-growth VC-backed companies. During my sabbatical, I've been reading a lot more about "alternative" forms of starting businesses. For example, I've found it really helpful to learn more about 37signals. This and this are two great podcast episodes where Jason Fried talks about what's worked for them. I've also found it helpful to read and learn about Sahil Lavingia's journey with Gumroad. He's written a book about it here. Pieter Levels has also been an inspiration for learning more about bootstrapped businesses. I loved that he recently vibe-coded a video game that's already started generating recurring revenue.

A biological connection to Porter's work

The world is a dynamic place. Each living system is in a constant process of change to maintain balance and fitness within its ecology. An organism's ability to cope with this dynamism and change is strongly linked to its ability to generate insight into its environment. These insights occur via direct experience. The most profound insights seem to be those that are simultaneously most applicable for a broad range of relevant phenomena, whilst making the fewest amount of assumptions. What's something business frameworks, spiritual systems of practice, industry best practices, etc. have in common? They're each a stale and perhaps ossified articulation of some embodied insight that a person or group of people have had via their direct experience with their environment. Specifically, at some point in time, someone had a systemic insight along their 4P stack of knowledge that allowed them to purchase a more optimal grip onto their environment. In the specific case of mystical experiences within spiritual traditions, I've written about the overall process here.

This is why mindlessly applying some framework to a situation often yields limited or negative results. We have to critically engage with the work, and attempt to unpack its underlying assumptions. We have to attempt to view the world from the lens of this framework along each of the 4Ps. That is, not just propositionally, but procedurally, perspectively and and via active participation. An effective way of doing this is to attempt to find connections between a given piece of work with insights generated by other fields.

Porter's work seems very related to our biological understanding of niche construction.

There are certain phenomena (e.g. living things) that can't be readily described via linear chains of causation. That is, linear descriptions where A causes B, which causes C, etc. Instead, we must rely on circular chains of causation that describe the co-evolution of processes rather than a linear description of events. That is, the state of process A at a given point in time is a function of the state of process B at a given point in time. And the state of process B at a given point in time is a function of the state of process A at that same moment in time. Just as how no man is an island, no living thing grows in isolation from its environment. Its overall genotypes are influenced by selection taking place over multiple generations and phenotypes are influenced by co-creation within that organism's life path. All of this happens via complex chains of circular causation with the environment. Ultimately, each organism must find a sustainable way of maintaining its metabolic expenditure in relation to its environment. A common strategy is for each organism to engage in differentiated activities that integrate in complex ways with broader ecological processes. This allows organisms to construct stable niches allowing them to continue sustaining their metabolic expenditure. That is, continuing to stay alive.

Indeed, humans are also living things that grow and co-create with our environments via circular chains of causation. Specifically, each of us has to contend with the inevitability of our metabolic expenditure. "Staying alive" is the base normativity which drives the behavior of every organism including humans. Unlike other organisms, humans have the psychological tools to reframe and expand the scope of what it means to be "alive" to better cope with our mortality. But that's a conversation for another day. The broader point I'm trying to make is that money and other abstractions of social value are ultimately overlaid on top of this base reality of the human organism. It's upon that reality that market structures are either consciously built or unconsciously emerge. This seems broadly independent of any specific policy or political orientation which seeks to govern the rules of each market. Again, at the end of the day, each human has to contend with their own metabolic expenditure and their machinery for ascertaining relevance within their subjective sphere of awareness.

I'm not sure if Porter consciously made this connection between markets in commerce and "markets" within biological systems. I plan on learning more about his body of work. But connecting these two ideas has offered me insights into the through-line that runs through each. One way to read Porter's framework is that he made ecological thinking legible to businesspeople. This is also likely why Porter's framework is largely silent on offering extremely concrete prescriptions around tools and practices. And why it seems to place such a heavy burden on a strategist's "creativity". That's not an unreasonable position for Porter to take. But by not going deeper into asking where "creativity" actually comes from, the average practitioner is left bereft of tools to actually proactively cultivate their overall creativity. Especially since it seems that there are deep connections between the pursuit of the proactive cultivation of creativity and the proactive cultivation of wisdom. I suspect this also partially accounts for why so few people seem to actively follow Porter's ideas. Or perhaps, they seem to follow his ideas sort of badly. All this is despite his ideas being widely taught in MBA courses.

How can I get better at strategic thinking?

This is the most common question I hear when I talk to other people in product strategy classes, or product management circles. It's a question that I've been wrestling with for a while too too. The meme below is my tentative conclusion/answer.

More specifically, I think that one's ability to engage in strategic thinking within the context of their individual lives is intimately tied to their ability to engage in strategic thinking within organizational contexts. Moreover, the biggest hindrances to engaging in strategic thinking seem to often be emotional and developmental. Especially within organizations largely staffed by people with the relevant educational background. We can shine a light on this claim via the thought experiment of the single-person company that I first introduced in this post.

Let's imagine a single-person company that has to somehow achieve competitive advantage in the market. But it only has one employee! So by process of elimination, the entire company's operational outcomes can be causally linked with the CEO's internal psychological dynamics. Moreover, every strategic pitfall that the company might encounter is likely causally connected with the CEO's emotional and psychological development in some way. That is, to the extent that they are "wise".

The world's major religions have spent millennia contemplating the common ways that people bullshit themselves. Note that I use "bullshit" in its technical sense articulated by Harry Frankfurt in On Bullshit. I might write a post in the future to explain this a bit more. To help their descendants lead better lives, these religions evolved prescriptions and norms on how individuals ought to conduct themselves. For example, the West has the ten commandments, the Buddhists have the pratimoksha vows or reflections on the three poisons that hinder enlightenment. Rather than viewing these ten commandments, pratimoksha vows, three poisons, etc. as a series of reified rules that one has to mindlessly follow, I've found it more helpful to view them as "provocations". For this specific discussion, we can use them to better unpack the causal relationship between the founder CEO's self-deception, and any strategic sub-optimality that they might engage in.

Connection between Buddhism's three poisons and the creation of bad strategy

Let's go into a bit more detail with Buddhism's three poisons, and how they might impair the construction of an effective strategy. For the purposes of our conversation, the three poisons are maladaptive craving, maladaptive aversion and ignorance/delusion/denial of the impermanence of life. To forestall any angry comments at the bottom of this post - yes, I understand that I've provided an oversimplified articulation of the three poisons. But I think it's good enough for what we're doing here.

I chose Buddhism for these examples below since it's what I'm most familiar with. But we could have just as easily used the normative backdrop from any other major religion. Also, I want to own my overall ignorance here. I'm still very much a student not just of Buddhism, but the other major religions. To my naive ears there seems to be a remarkable overlap between the observable behaviors they all seem to encourage, specifically around love, compassion and the pursuit of wisdom.

Each of the examples below is a hypothetical scenario. Each features a separate instance of the three poisons impairing the CEO from forming an effective strategy.

Grasping towards prestige

Our CEO empirically understands that their widgets could be sold with a far higher margin if he did cold calls to directly sell them to their customers. But he has a CEO friend from business school that sells another type of widget in a totally different market via big-box retailers. This friend posts incessantly about his company's growth on LinkedIn. Perhaps he also takes selfies with attractive people on Instagram and Snapchat. Perhaps he brings it up every time he catches up with our brave hero. His business is booming, and increasing headcount at a remarkable rate.

Our CEO feels very insecure about all this. But also empirically understands that attempting to sell via big-box stores would instantiate an undifferentiated value chain with his competitors. It's also not clear that it would succeed, because it's not clear that it even makes sense for our hero's market. Our hero also understands that his friend is in a totally different market. It may not make sense to copy what he's doing!

The cold calls are empirically extremely effective albeit uncomfortable since they entail lots of rejections. These rejections deeply affect our hero's baseline insecurities. Each rejection feels like another punch in his gut about what a "failure" he is. Moreover, when he engages in BD conversations with the big-box retailers he feels more "productive". Each BD cycle is fairly long, conversations are non-committal. So it doesn't feel as bad as cold-calling and getting a ~10% conversion rate.

His business school reunion is coming up. He's been working on this company for a few years now and he'd really like to toot his own horn there. He just wants a win that will help him seem as "successful" as his friend. He knows what he must do to actually "win". That is, do the cold calls. But he just can't bring himself to do it.

So for now, he chooses the worse option. Because at least in the short term, it allows him to cope with his insecurities and feel better about himself.

Aversion from difficult conversations

Our CEO's homegrown widget business is taking off. During its growth, he organically instantiated two different offerings with two very different value chains. One of them is very differentiated and makes good profits. It's such a unique way of tackling the problem that he's not worried about anyone independently coming up with something similar. At least, for now.

The other value chain is extremely undifferentiated and his margins seem to get far worse every few months. But the supplier for this value chain is a close friend, and our hero finds navigating boundaries very challenging. The extra overhead of maintaining these two value chains is also a tax on his mental health. It's started bleeding over into the overall running of the business. That is, he's started ever so slightly dropping the ball on the more profitable value chain of his business.

He's working on this company himself. If he had more time back, he'd be able to substantially increase his power within the more profitable position. And perhaps differentiate the activities of his business even further. The other value chain isn't particularly lucrative for his friend either. On some level, the friend understands that our hero will stop their business at some point. But our hero's never brought it up. And it's good money! So the friend's happy to keep it going.

The "right" thing to do for our hero's business would be to have a conversation with his supplier friend. But he finds such conversations uncomfortable, especially with his friends. He finds it a lot easier with strangers, but is often averse to "rocking the boat" when it comes to his friends. Even when it often overextends him.

Having a conversation with his friend is so triggering for him, that it's not even a realistic or viable option within his sphere of awareness. But with every passing week, he feels more and more overwhelmed. As he feels more overwhelmed, he starts to feel more anxious about the viability of the company itself. In the absence of any particular practices to unpack his feelings, he continues keeping things exactly as they are.

Delusion around the impermanence of market dynamics

Our CEO has built a search engine for restaurants in NYC. Unlike services like Yelp which rely on user-generated content, our fearless hero has physically visited every single one of these restaurants and meticulously collected lots of little details about them. His discerning taste on what is relevant for his users has allowed him to create a million different filters that are far superior to what Yelp offers. This has led to some extremely strong retention of traffic which he's been able to translate into a very profitable business of placing advertisements. He gets really good conversions on these advertisements. Rather than engaging in an automated auction, he carefully selects the ads himself based on his sense of taste.

He's been doing this for a long time. He keeps his database fresh by hiring gig workers and the business now largely runs itself. For the past couple years, he's been living as a digital nomad. These days, his most pressing concern in life is finding a dope beach to chill on. He rarely fixes bugs or other issues on the website anymore. Traffic has remained good and life is good!

ChatGPT launched a few years ago. He can see how LLM APIs could potentially disrupt his value chain in a number of ways. For example, it's becoming easier for developers to build extremely personalized experiences using the inherent factuality of the models, combined with their ability to read lots of webpages and to effectively render human judgements.

In the best case, it would mean that he no longer has to hire the gig workers and he'd generate even more profits. But in the worst case, it would mean that anyone can vibe-code something "good enough" as what he's already got. His overall value chain would cease to be viable and he'd have to construct another one from scratch.

In this worst case scenario, he'd have to make non-trivial changes to his lifestyle. Not only did he believe that that this gravy train would last forever, it's become a core part of his identity. If the business folds, he has serious self-doubts about whether he could do something like this again. He's been chilling for so long that he feels rusty. He's creatively blocked and just doesn't feel motivated anymore. Yet he's also deeply unwilling to work for The Man, or make any other compromises with his life. When he started this whole business, he knew it wasn't permanent. But over the years, that's what he unconsciously trained himself to believe.

Now he has to come face-to-face with the impermanence of not just his business, but the very ground upon which he's erroneously built his self-worth and identity. He could face this reality head-on. But he can't bring himself to do it, so he decides to stick his head in the sand.

What are concrete things I can actually do?

If you've reached this point of the post, an unsettling realization might be dawning upon you. The problem of getting better at strategic thinking is extremely connected to the problem of getting better at overcoming your own self-deception and limiting patterns of behavior. As the case studies above illustrate, you can't "solve" this the way you might "solve" a maths problem. That's because these maladaptive behaviors aren't operating at a purely conceptual/propositional level. Our brave heroes in the case studies above struggled to make "smart" strategic choices for the same reason that most people (including myself) struggle to regularly eat their vegetables or go to the gym. It's not merely about holding the right set of beliefs. It's about the cultivation of character. Or rather, the cultivation of wisdom. It's the honing in of your relevance realization machinery against a specific hierarchy of values. Although, I don't want to dismiss the many times that conceptual ignorance can stymie strategic thinking. For example, not knowing specific industry knowledge, etc. However, I've seen many teams staffed by largely intelligent people commit what seem to me like strategic blunders. Most of these seemed to stem from their inability to wisely and clearly engage with the real patterns they perceived in the world.

Even though there isn't a clear formula for growing wiser, that doesn't mean there are no resources for proactively doing so. Again, one could argue that each religion has been a millennia-long conversation on how one can grow wiser. In today's world, therapists have taken the role of shamans/wise men from eras past to facilitate personal transformation. I suspect that therapy is an excellent place for most people to start. This post describes a process that has helped me on my own therapeutic journey. But really, you're going to need to increasingly step into the driver's seat of your own life.

My general motto is something like - "If something isn't working, fearlessly attempt to change it. If something is working, don't change it. And make your peace with what you have the capacity to change, and what you can't". In that vein, it's been extremely helpful for me in the past to run lots of time-boxed experiments with my life.

It's also been helpful to map this single-person company thought experiment to my immediate life. For example, sometimes I'll look at my calendar from the last week, including both personal and professional commitments. Here are some questions that have been helpful for me to ask myself:

Imagine a future you do want as well as a future you don't want. Specifically, imagine these futures in terms of concrete calendars. What is the delta between where you are and what you want, and which activities are least aligned?

You'll never achieve mastery at everything, and you'll never please everyone. Consider the importance of clear trade-offs when crafting a strategy. In what ways are you straddling, and how is that reflected in your calendar? Can you craft a strategy that will afford mastery along any specific activity?

What are the key strengths in your value chain (i.e. activities along a calendar), and how can you amplify them? That is, how can you engage in a much more self-authored and differentiated value chain/calendar than the average person in your industry? Specifically, one that really amplifies your power?

Our capacity to imagine the future

Something I talked about in this previous post is the important role the proactive cultivation of wisdom and insight is going to play as the marginal cost of generating code goes towards zero. But wisdom and insight are heavy words. Let's take a step back for a moment. Where do good ideas actually come from?

Anyone who's spent any time practicing any sort of meditative practice will realize that our field of awareness is extremely mysterious. Thoughts can sometimes seem to appear and disappear without any clear pattern. These thoughts might be reflections of the past, observations of the current moment or projections into the future. In my experience, it's not so much that I have good ideas, as much as a sufficiently compelling idea drops into my field of awareness and I decide to just believe it and run with it. To solve any given problem, we need to first bring the solution into our field of awareness, and then orient our body towards instantiating that solution into the world. At the time of conception, the solution is just that. It only exists in our minds, since we haven't actually changed the atoms in the world to instantiate that solution yet.

This capacity to imagine what doesn't yet exist seems like an indispensable part of problem solving. In fact, it seems that this imaginal space is causally related not just to any propositions that might enter our field of awareness, but rather the entire 4P stack of knowledge that we might possess. The field of possibilities within a person's imaginal space seems to be a function of the overall evolution of an organism's life.

I don't actually know enough about the cognitive basis of the imaginal to say anything interesting to our single-person thought experiment. Ditto for connecting it to my overall research project around building an AI that can instantiate and run companies. I just wanted to call it out here so that it finds purchase in your minds. Before we can talk about the imaginal in relation to this project, we will likely need to explore a few ideas related to autopoiesis. I'll write a few posts to explore this soon.

Closing thoughts

At this point you might be wondering - but wait! Most "real" companies have more than one employee and have to contend with their collective psychology. You're right and I'm not trying to pull a fast one on you. This thought experiment was deliberately constructed to shine a light on the causal relationships between a company's internal psychological dynamics and its operational effectiveness. The psychological dynamics of a group of people is often necessarily more complex than the dynamics within a person. However, the other reason I wanted to start with a person is because I believe that there's a deep continuity between the dynamics within a person and without. To make that connection clearer, I'll need to draw from a lot more CogSci and philosophy than what I've presented here. I'll leave that for future work.

Until you make the unconscious conscious, it will direct your life and you will call it fate.

- Carl Jung

There seems to be a natural curriculum with which we experience our lives. We live out our lives in patterns. Not all of these patterns are necessarily adaptive or relevant throughout the course of our lives. Until we make these unconscious patterns conscious and find a way to transcend them, we're forced live them out again and again. In some sense, this is related to what I think a person's religion is. An individual's religion, that is, the thing that binds their cognition is the set of things their patterns are oriented towards.

Humans are social primates and our perception of reality, and the environments we live in are mediated by cultural forces. Future posts will dig into this a lot more, and relate it to market outcomes.